The now almost vanished Roman Palace (Praetorium) at Castor was one of the largest Roman buildings in England. Its role is uncertain, however it was a huge building with significant importance, probably administrative.

Built in 250AD it was close to the site of Durobrivae. It was abandoned in 450AD and some of its stone is incorporated into the church.

Durobrivae is where the Water Newton treasure, the oldest known communion plate in the Roman Empire, was found. Some scholars argue that this silverware was from the Praetorium at Castor and hidden from raiders by burial. See the work done by Castor Primary School pupils and friends click here > Castor Romans

The term Praetorium in this case means a Roman governor’s residence or headquarters. but its function is still not fully understood. There have been several theories and suggestions over the years.

The term Praetorium in this case means a Roman governor’s residence or headquarters. but its function is still not fully understood. There have been several theories and suggestions over the years.

One supposition is that it was the residence of a Roman provincial governor during the third century AD. Castor would have been in Britannia Superior for most of the third century, then in the province of Maxima Caesariensis for most of the fourth century.

Another possibility is that the building was the headquarters of the Count of the Saxon Shore, a Roman military commander post possibly created by Constantine I during the fourth century AD, whose job it was to govern the military defences of the southern and eastern coasts of Britain from barbarian (Saxon) attacks.

However, all of this is conjecture and there have not yet been any conclusive clues as to the identity of the building’s occupants and its purpose. (Above: Foundations still visible in Stocks Hill near the village school)

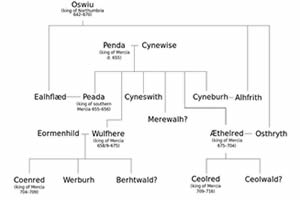

By 654, a marriage was being negotiated between Peada, son of Penda, and Alhflaed, daughter of Northumbrian King Oswy. The Northumbrian king stipulated that first Peada must accept Christianity. He appeared prepared to do so whether he won the hand of the maiden or not and was baptized by Finan, the Celtic Bishop of Lindisfarne.

The royal couple returned to Mercia and may have taken up residence on the site of the huge but derelict Roman Praetorium on the terrace at Castor.

Peada had already been appointed by his father as sub-king of the Middle Angles, whose province covered Northamptonshire and Leicestershire.

Peada’s sisters, Kyneburgha and Kyneswitha came south too and established a convent here in Castor in the Celtic tradition but possibly on the site where Romano-British people worshipped to the Roman tradition. (Above: Saxon carving likely to be from Kyneswitha’s tomb)

The Celtic Christian foundation at Castor was established by Kyneburgha, aided by her sister Kyneswitha. After their deaths circa 7C a shrine was established in this Saxon minster church, to the two sisters and it became a place of pilgrimage. Later,outlying chapels were built at Ailsworth(no longer exists), Sutton, Upton, Milton and Marholm.

Viking raids, probably on several occasions from 870AD onwards ruined the fabric of Castor Church by 1012. Kyneburgha’s remains were removed to Peterborough Abbey for safe keeping by Abbot Elsinus.

The Normans rebuilt the church, re-using some of the Roman and Saxon fabric especially for the nave, and it was re-dedicated on 17 April 1124. This re-building gave us the nave, the remarkable tower, most of the transepts and the capitals that we see today.

By 1330 the church was almost complete as it is now seen, with the exception of alterations to the roof line about 1450, including the magnificent carved angels and other figures. These were restored to their former glory in 1973.

St Kyneburgha

St Kyneburghain whose name the church is uniquely dedicated and her sister Kyneswitha, were believed to be the daughters of the heathen King Penda of Mercia and his wife Kynewise.

Kyneburgha married Aldfrith son of King Oswy of Christian Northumbria at the same time as her brother Peada married Aldfrith’s sister Alchflaed.

Celtic Christianity flourished in that part of the world and it was likely that this latter union depended on Peada’s conversion as Christian, which subsequently influenced Kyneburgha.

Following her husband’s death, she came back to Mercia and established a convent among the ruins of the Roman palace here in Castor.

With its unique dedication to St Kyneburgha, it is considered by many to be among the finest 100 churches in England.

With its unique dedication to St Kyneburgha, it is considered by many to be among the finest 100 churches in England.

Following the Saxon church’s sacking by the Vikings in the 9C, it was rebuilt in Norman style and dedicated by the Bishop of Lincoln in 1124. Outside above the priest’s door in the south wall of the chancel, is a rare inscription commemorating the event.

The tower is the church’s crowning glory built in three tiers. The lower tier with three bell arches is headed by very fine fish-scale pattern – all of which is magnificent work and nearly 1000 years old.

The spire and north aisle were added between 1310 and 1330. The nave’s magnificent angel roof was added about 1450.

EDMUND TYRRELL ARTIS F.G.S., F.S.A. 1789-1847

Edmund Tyrrell Artis was born at Swefling (near Saxmundham, Suffolk), the son of James and Mary Artis (nee Watling). His father was a carpenter or cabinet maker, and although Edmund was later described as being born in “easy circumstances”, his mother was illiterate, and both parents died poor.

In 1805, Edmund came to London to work for an uncle in the wine trade, but by 1811 he had opened his own shop in Dorset Street, W.1, as a confectioner. In the same year he married Elizabeth Poole at St. James, Piccadilly. She came from the Bristol area, and a year later they had daughter, also named Elizabeth, but known as Betsy.

In 1813 it would appear that one of Edmund’s iced cakes, in the shape of a fantastic castle attracted the attention of the 4th Earl Fitzwilliam, who took him into his household, and by 1816 he had risen to the position of House Steward of the Earl’s seat at Milton then in Northamptonshire. Artis was clearly a man of multiple talents, for in 1816 he painted a portrait of the Earl in oils, and he made the acquaintance of John Clare the poet in 1820, who freely acknowledged the debt he owed to Artis on matters of Natural History. This interest must have been the stimulus for Artis to start collecting fossils, first from the gravels of the river Nene terraces, and soon after from the Carboniferous deposits found in the Fitzwilliam’s coal mines, principally those of Elsecar in South Yorkshire. This led to his election as a member of the Geological Society in 1824.

Concurrently, he discovered a mosaic pavement in the churchyard at Castor, near Milton, and from then on he began a long investigation of the Roman remains of the area, and from 1823-5 published the first four parts of the current volume by subscription, and was rewarded by being elected to the Society of Antiquaries of London.

In 1826 he published Antediluvian Phytolology, which contained illustrations of his collection of Carboniferous fossils, and in that year, he left Milton, apparently in minor disgrace over a sexual indiscretion (which was probably his second offence, a record existing of an earlier illegitimate child, known as Edmund Hales). In October of that year, he held an auction of his Castor household effects, including a Clementi piano, and a Poussin painting, which he appears to have inherited from a relative.

His relationship with the Earl Fitzwilliam could not have been irretrievably damaged, since in that year, he both designed a commemorative medal of the Earl, and on quitting Milton, he bought the Doncaster Race-Club House, which was a lodging place for the ‘great and the good’ during the St. Leger race meeting each September, which was under Fitzwilliam patronage. He also became Secretary of the Race Club, which organized events. He sold his fossil collection, some of which remains today in the Natural History Museum. The remaining parts of ‘The Durobrivae’ were published in 1827 and 1828.